What if we viewed education as a giant treasure hunt through God’s universe? What if we looked for all of the ways that our academic subjects add to our knowledge of God’s attributes? What if we viewed the twin goals of education as falling down in worship and rising up in service?

It is the glory of God to conceal a thing: but the honour of kings is to search out a matter. (Proverbs 25:2, KJV)

The Treasure Hunt of Christian Education

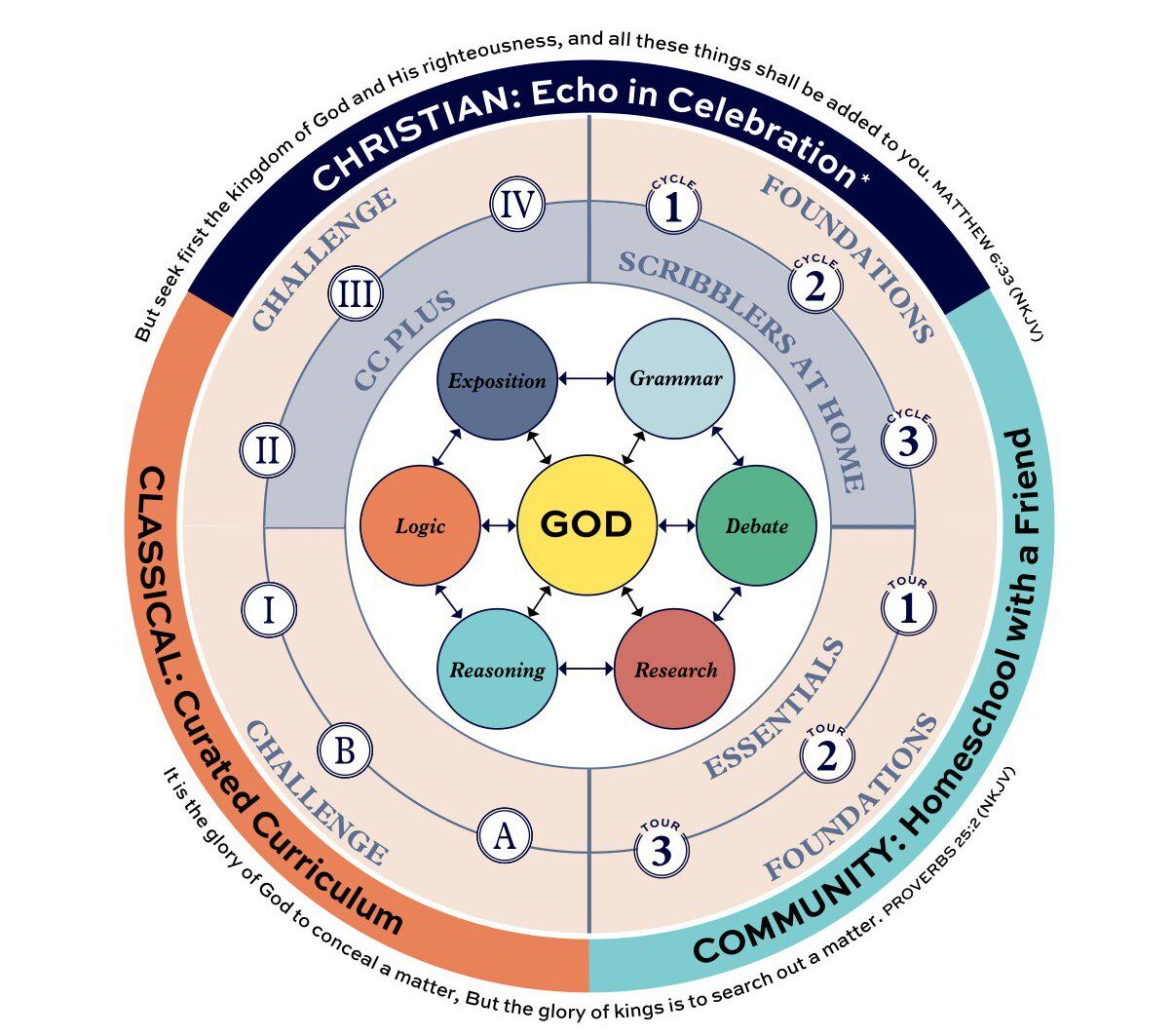

If parents are seeking a thoroughly Christian education for their children, the search for these treasures offer us a broad and inspiring definition of a Christian education. First, we acknowledge that God has created a universe in which the parts are inherently connected to one another and to Him. Second, we see that God, not the student, is firmly at the center of education. Finally, we approach studies with wonder, seeking the bright and valuable treasures that God has hidden for us to uncover.

A modern education is inherently fragmented. If one discards the idea that God created the universe and personally holds it together, there is no unity of knowledge. The universities were called universities because they taught students to seek the fundamental, universal truths of human existence. The universe is called a universe and not a multiverse because it is one whole with many parts working together.

A modern education places the student at the center because the aim of the modern education is job education. Picture a solar system diagram with the student at the center and subjects in orbit around the student. Each of the subjects offered up the student – math, foreign language, English, science, history, and a dazzling array of electives – are in discrete bubbles that are served up to the student in fifty-five-minute increments by six or more different adults. The student would have to work very hard to discover the connections between philosophy and math, history and science, or literature and politics. The student in the modern secular education has been taught that faith and school are separate from one another. She would have to work very hard to see how subatomic particles or the double helix structure of DNA have anything to teach her about the attributes of God.

A Christian education usually takes the modern education model and adds Bible verses to lesson pages or adds chapel or a Bible study course. The student is still at the center of education, and the subjects are still disconnected from one another and from God.

A robust classical, Christian education starts with a completely different model. If you again picture a solar system, God would be the center. The subjects would again orbit around the center, but this time, there would be arrows going out to and from God, and there would be arrows going back and forth between each of the subjects. Now, the student sees how God has ordained each of the subject areas, and how the study of each area teaches students more about God. In addition, the student Is encouraged to make connections between the subjects. In the Classical Conversations Challenge program, Tutors are with the students all day long so that conversations can naturally explore the connections between poetry and music theory and math.

The Catechesis Wheel

To illustrate this idea, Classical Conversations has developed a visual called the catechesis wheel. The Greek word catechesis simply means oral instruction. People usually associate the word with church classes in which the teacher (the catechist) asks a question from the curriculum (the catechism), and the student, (the catechumen), responds with a memorized response. The goal of catechesis is to prepare the student for membership in the church. For example, one question from the Westminster Confession is “What is the chief end of man?” The catechumen responds, “Man’s chief end is to glorify God and enjoy Him forever.”

It has been said that there are two ways to know God, through His Word and through His world. It is possible to extend the idea of catechesis to oral instruction in any field of knowledge. In the Classical Conversations Foundations program, students practice catechesis with history sentences. The parent or tutor gives a prompt or asks a question. For example, in history the parent or tutor says, “Tell me about the Magna Carta.” The child or class answers, “English King John signed the Magna Carta in 1215, limiting the king’s power. Later, England’s King Edward III claimed to be king of France and began the Hundred Years’ War in 1337.” In science, the parent or tutor asks, “What are some parts of the food chain?” The student or class answers, “Some parts of the food chain are producer, consumer, and decomposer.”

On the outside edge of the catechesis wheel, there is an arrow showing how the process of education begins. It begins with building a storehouse of knowledge, both facts and stories about God’s world and people. Then, students move beyond facts and begin to wrestle with ideas and notice repeated themes. Here, they can begin to see how the subjects teach them more about who God is. The arrows pointing back and forth between God and the subjects begin to make sense. Then, students move toward rhetoric, toward wisdom and understanding. Students are now able to make connections between the subjects. Repeating the process again and again results in worship and service. The word doxology literally means a word of God’s glory or speaking God’s glory. The culmination of study should be to echo in celebration of God.

Integrating Subjects in Upper Challenge Classes

This idea of the wheel and integration of subjects may be best illustrated by a peek into a handful of upper Challenge classes.

In debate, we spent time comparing the American and French Revolutions. Our discussion of the French Revolution caused us to talk about the role of the French mob during those years. Unlike the American Revolution in which the revolutionaries quickly established an orderly government based on law, the French Revolution produced no clear Constitution, but instead, devolved into a totalitarian state in which mobs roamed the streets arresting citizens and turning them over to be executed by guillotine. This led us back to Shakespeare once again as we briefly touched on the role of the mob in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. Talking about the fickle and violent nature of mobs then prompted us to consider how the Federalists, particularly John Adams, feared that the new U.S. democracy could quickly descend into mob rule.

In our poetry class, I had my students read an essay called “Seeing” from Annie Dillard’s book The Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. I wanted to challenge them to be still, to see nature, to reflect on their own spirits as well as on God—in other words, to be poetic. Her essay is rich in similes and metaphors. We paused to examine some of these in detail and to discuss Jesus’ use of metaphor when He calls himself the vine, the bread, and the wine. I asked them to consider why contemplation of nature and poetry are so often linked (think about the Psalms of David). How does knowing the names of particular trees, birds, and fish impact our understanding of who God is? How is naming things poetic? Why did God have Adam begin his “education” by naming the animals? What does this say about our studies of biology or chemistry? What is the connection between science and poetry? If we are made in His image and we are poetic, is God a poet?

In Latin, I asked students to give a verse or a word from the Gospel of John in Latin that stood out to them that week. My normally quiet daughter was the first to respond by saying she was surprised to see the word “ratio” in Scripture. We looked up the word in our Latin dictionaries to remind ourselves that it is a third declension noun meaning “reason or explanation.” We talked about how it is the root of both ratio in math and rational in logic. All day long, we returned again and again to this word. We set up ratios in both math and chemistry, we examined the ratios between notes in chords in music theory, we talked about man being “noble in reason” in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. We talked about how the French Revolutionaries, influenced by the spirit of the age of Enlightenment, put up statues of the goddess of Reason in French churches to show that reason was more important than faith.

These three separate community days with different groups of students in different years demonstrate the power of the classical Christian education that is illustrated in the catechesis wheel. By being together with one adult mentor for all subjects over a number of weeks, the students were able to see the connections between history, literature, Scripture, poetry, music theory, math, chemistry, and Latin. Those discussions led to a deeper understanding of the beauty of God’s universe and thus of God’s attributes. Knowledge led to understanding which led to wisdom which led to worship.

Listen to the founder of Classical Conversations, Leigh Bortnis, as she explains the Catechesis Wheel for classical learning: