I do not like it when people say a movie is boring. What they mean when they say it is boring is that they are not able to focus their attention on the movie. This is quite a different thing from the movie being boring or otherwise. When people say a movie is boring, they are saying a lot about what kind of movie viewers they are, and very little about the characteristics of the movie itself.

The people I am talking about are usually teenagers. They say, “I didn’t like that movie; absolutely nothing happened.” This is actually a valid sort of criticism; it is what I say about movies I hate, because in most movies that are made, in my opinion, absolutely nothing happens. The difficultly with this statement, however, is that it can be applied both to bad movies and to good ones, and for entirely different reasons.

Here is what I mean. When talking about whether or not anything “happened” in a movie, it is important first to understand the distinction between story and plot. Drama critic and theorist Eric Bentley defines them this way: To say that the king died and then the queen died is a story. However, to say that the king died and then the queen died of grief is a plot. Story concerns concrete happenings. Plot concerns abstract happenings: personalities, motivations, whether certain decisions were mistakes or not, what makes the good guy good, what makes the bad guy bad, and so on. Plot is the story behind the story. All movies have a story—a succession of events. Good movies have rich plots as well as stories.

Understanding the difference this way, you can see how the same story could, conceivably, be written by different authors, all imbuing it with different plots. Take, for example, the historical event of Julius Caesar’s assassination. The story runs thus: Caesar makes moves to overturn the existing political structure, and a handful of other politicians decide to kill him before he can accomplish it. Given these events, William Shakespeare construed the following plot: Caesar acted the way he did because he had become intoxicated by his own notoriety, and Brutus joined the other assassins because he was willing to sacrifice his friend’s life—and even his own life, if necessary—to preserve the republican culture he loved so much. Another playwright could relate the same events, but write a different plot, such as: Caesar was a misunderstood reformer who was destroyed by jealous personal enemies.

We miss the distinction of plot and story today because (with the exception of remakes, and these are often spaced decades apart) we usually only ever see a single author’s rendition of any particular story. We therefore assume that a particular plot is inseparable from a particular story. It is not. Imagine a scenario in which a movie told a familiar tale in one way, and the next year another movie told it in a completely different light. This was the situation in ancient Greek theater. The audience members all knew that Oedipus married his mother, since Oedipus was a historical king. The reason to watch plays about him (or anybody else, for that matter) was to see what kind of man the playwright made Oedipus out to be.

So, to bring me back to the point—namely, whether movies should be called boring or not—there are two kinds of movie viewers: those who watch for story, and those who watch for plot. I admit that many of the best movies have stories that are not, in and of themselves, exciting to watch. Most of the “action” that takes place consists of talking, and so, in a sense, a more impatient viewer than I would be correct in saying that very little “happens”—because what is happening is all plot, and this is usually invisible. Slow, mundane events are the kind of “nothing” that is allowed to happen in a good movie.

On the other hand, a movie whose events are all exciting ones, such as explosions, kisses, scary surprises and the like, is not, in itself, exciting to watch either—it is just that these kinds of attention-hijacking events make us think that it is. In fact, I could go to such a movie and rightly say that nothing “happened.” I would not mean that no events took place. Rather, I would mean that there was no overarching meaning, no message, no character development behind the events. This is the kind of “nothing” that happens in bad movies (and woe to the movie that makes this mistake and also lacks exciting events to watch).

The kind of movie viewer who watches for plot gets the better side of the deal, for, by observing and “getting” the plot, his eyes are opened along the way to the interest of the events in the story, no matter how mundane those events might have appeared at first. He has learned to be interested in something in which it is difficult to be interested. I submit that this is called refinement. Those who watch only for story—for the instant gratification of the events the movie includes—have not been refined as people when the credits roll.

This explains why it is so difficult for patient, attentive moviegoers to have conversations with impatient ones: both of us hate the kind of movie where nothing happens, but we point this accusation at completely opposite sorts of films. I hate Twilight, not because its events are as boring as paint (even though they are), but because there is nothing interesting or even non-obvious going on between the characters—because “nothing” is happening. In contrast, I love Reservoir Dogs, not because the events in it are exciting (in fact there are only a few really exciting moments and all of them are flashbacks,) but because every twist and turn of the story is driven by the invisible personalities of the characters. You have to be really attentive, to really watch the movie, in order to see what is happening.

I was raised really watching movies. I do not know how or where I acquired my tolerance for “boring” film, but it came early on—a piece of art friends would hastily dismiss as weird or boring, I would patiently observe in order to discover hidden mysteries. Occasionally this does not pay off, but I still grant the benefit of the doubt. To this day I like films like Rashomon, The Seventh Seal, and 2001: A Space Odyssey, because they have more happening in them than any others I have seen.

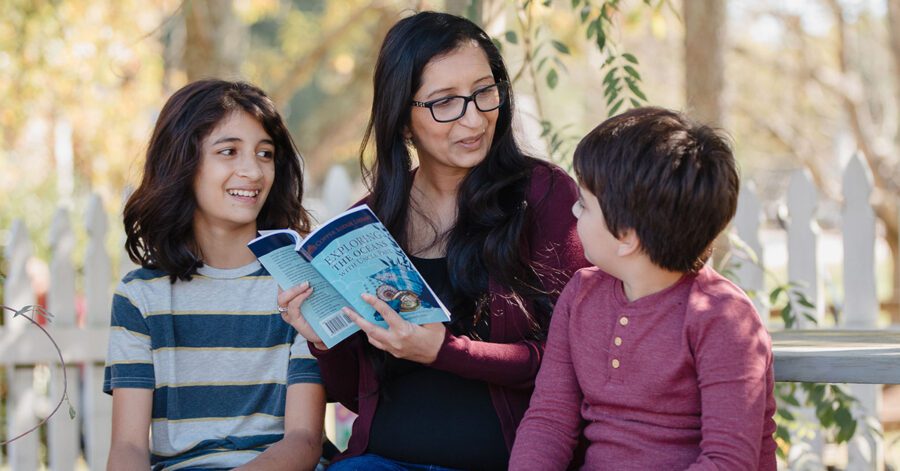

So, what this means for watching movies with your students is that, as with dry wine or bitter cheese, liking good movies requires time and guidance. When I run my summertime film class for teens, I find it is highly effective to ask them questions about what motivated the characters to do such and such, or why the director chose to focus the camera on one particular detail (why, to take a recent example, did the director give us a close-up on a soldier’s absentminded attempt to wipe blood off his hands with a piece of cloth too filthy to do the job? Why include this in a movie about the emotional scars of war?). A change comes over the room. Students have been asked a question they may have never considered before. Soon everyone has insights to offer far beyond the usual banter about which parts were funny or “cool.” By being treated like refined art critics, students feel they have the permission to think like such critics. The remarkable thing is that, just by asking these questions, you will start thinking like one, too.

Here are some ways to get your teens serious about their movie watching:

• Ask what a character means when he says something. Ask what the director means when he shows something. You can do this with individual scenes at first, or you can use movies that are “fun” enough to be easily digestible.

• After watching a movie, read a Christian movie review. Christian reviewers all have an opinion about what the message of the movie was. Discuss whether you think the reviewer has summed it up correctly, of if he has missed something crucial.

• Point out second-rate plot decisions when you see them (for example, “Wouldn’t it tell the story better if Jasper were having this showdown instead of Edward, since Jasper has so much more in common with the villain?”) and then discuss whether or not these decisions then make the movie itself second-rate. Analyzing plot mistakes in this way will help teens build an idea of what good storytelling looks like.

• Ask, “What is the theme of the movie?” This is different from a summary of the events!

Do not take this article as an injunction to stop watching certain kinds of movies. Rather, take it as an injunction to stop a certain kind of movie-watching; watching a good movie can be a healthy experience, but watching any movie well is an experience which enlarges the soul and mind. At the very least, do not let your children say, of a non-explosive movie, “There was no plot” (unless, of course, there really was no plot). Instead, teach them to say, “Appreciating that plot required more concentration than I wanted to invest.” It is okay to feel bored, but movie viewers should be honest about what is really going on. Teach your teenagers to be refined—to enlarge their souls and their minds—by the movies that they watch; teach them how to watch movies well.