I don’t remember why we were talking about math curricula, but Julie, a friend of mine who home-educates her children, was clearly frustrated with solutions manuals and answer keys.

“They give you a few steps to get started, and then abruptly jump to the solution with a bunch of steps missing in between, and you have no idea how they got there. Suddenly, they’ve handed you a fully rendered panda.”

Well, I was empathizing with her as she talked about missing steps, but did she just say “panda”?! And not just panda, but “fully rendered panda”? Talk about a bunch of steps missing and having no idea how a conclusion was derived–I was there!

“What did you say?” I spluttered. “Did you say panda? Fully rendered panda?”

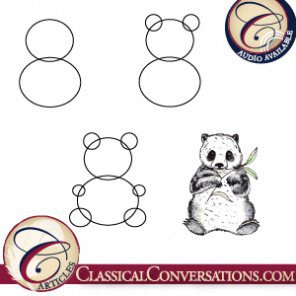

“You know those learn-to-draw advertisements, where they show you how to draw some animal or other, like Sparky, with a few easy strokes?” She fished out her cell phone. “There is one example where they show you how to draw a panda. The first picture shows how to draw two circles for the head and body. The second picture shows how to draw two circles for the ears. The third image adds four circles for the feet. But then the fourth and final picture is of a fully rendered panda, fit for his cover shoot for the National Geographic.”

She pulled up an example on her iPhone to show me what she meant, and I burst out laughing. The first three images were nothing but circles, even an artistic klutz like me could draw them. But there was no possible way one could progress from those initial fat, happy circles to the final product of a fully mature adult panda, in profile, and on the prowl; ready to lead her cubs expertly from the den to the wild.

There is an undercurrent of fear among some parents, tutors, and directors that to be effective lead learners in our communities, we need to be that fully rendered panda. Complete. Fully formed. They hear the words “lead learner” but they think “expert.” They think they must master the material and know all the answers. Surely, this is where hard study ought to kick in, right? While it’s true that man, as a rational being, is expected to use his mind well, he is not primarily a thinker, or primarily a believer, but primarily a lover. Don’t believe me? What were the two greatest commandments Christ gave His disciples? To “think on” the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind? To “believe” thy neighbor as thyself? No, both commandments charge us to love. A classical, Christian education will train children to order their loves and affections rightly by training their hearts and minds, and turning their dispositions towards the true, the good, and the beautiful. To train the mind but to neglect the heart is to starve the soul. The lead learner is someone who does not fear, but loves.

The first love of the lead learner is the love of student. Not a friends-y, pals-y kind of love but a love that is grounded in submission to the soul-needs of the child. What does that look like? For a start, it can look like hospitality, a warm welcome, and kindness. At home or on community day, how do I start our time together? Do I begin the day in prayer, or do I leap into the lesson? How do I act in the room– am I bowed in fellowship together with my children or students, or does my manner suggest that I stand and fall by myself, grounded by my own thinking and reason? Do I order our time, our space, our language, and our practices to inculcate a love for each other and things we ought to value, or do I insist that we “get the work done”? Do my children or students see me as the one they can trust to learn from, or as the one who will tell them what they need to know? The lead learner demonstrates love of student from a stance of submission, not from a posture of fear.

The second love of the lead learner is love of learning. Not an expert-y, know-it-all kind of love, but a love directed toward wisdom, cultivated in the Wisdom that became flesh and dwelt among us, whom we are called to imitate. Wisdom acknowledges that there are things we can know, people we can trust, things we can imitate. What does that look like? How does it begin? Wisdom oftentimes begins in wonder, but it is a directed, intentional wonder. Do my children or students see that I am concerned with covering mundane material, or with recovering transcendent values of truth, goodness, and beauty? Am I concerned with covering a curriculum, or with uncovering the wonder within the curriculum? What if our classrooms looked more like museums, where the parent, tutor, or director, like a museum curator, leads students from wonder to wonder? The lead learner demonstrates love of learning through imitation and wonder, not through fear.

A lead learner should not expect to be that fully rendered panda, because a lead learner never fully “is”; a lead learner is always “becoming”: always submitting, always uncovering, always loving, always leading from wonder to wonder, always approaching the ideal—but never becoming fully rendered (at least, not this side of heaven). The fear of a lead learner can be centered on self or directed inward, but just as Christ poured Himself out for us, the love of a lead learner is self-giving love. Part of the curriculum, of the pedagogy of learning, is living and modeling that vulnerable life in front of our children or students. For a time, all they may see are the fat, happy circles of our efforts; they may see the suggestion of the final image approaching, but we need never be concerned that we are not fully rendered. That is not what we are called to be.