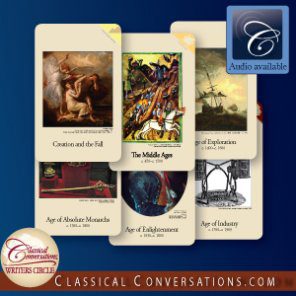

I just opened my new Classical Conversations history cards and I just love them! They are beautiful! I am reading Abolition of Man and Climbing Parnassus, and both are convicting me to immerse my children in truth, beauty, and goodness. The history cards are one of the ways I am going to do this. Each card links artwork with history. Art not only illustrates events, it reflects the worldview of the artist which may be unintentional on the part of the artist, and of course, it hints at themes which the artist intended to communicate about the event.

Families new to Classical Conversations sometimes ask, “Where is history in the Challenge programs?” There is not a textbook titled World History anywhere in the catalog, so how could we possibly learn history? We put the history timeline into the students’ long term memory during the Foundations program. We also spend the Foundations years listening to and reading about historical events in chronological order. However, the significance of the timeline is not their place in the Foundations program. It is integral to the Challenge program. This year I will be reciting the new timeline with my Foundations-age child and my Challenge-age children so that they can see how their studies fit into the history of man. Many of the new cards are events studied in Challenge so even though it is not listed as a requirement for class, my tenth grader and my eighth grader will richly benefit from becoming familiar with the new timeline—in beauty and in truth.

Once the timeline becomes a part of us, we are free and able to think about the events in terms of ideas, not just time. We are liberated from the unit study and we begin to study history, literature, and science by using ideas. We can compare ideas, events, and man’s choices from many different time periods and geographic locations. For example, in Challenge I we study the ideas of freedom, but we are not limited to the events of the Civil War in a textbook. We read what Martin Luther King, Jr. said about freedom during the civil rights movement and compare it to what the founding fathers said about it in American documents, and also to what Chuck Colson experienced when he was not free, but imprisoned. We discover that freedom has been difficult since the beginning of time, but it is worth all of the trouble—perhaps even worth dying for—perhaps worth fighting for today.

This emphasis on ideas allows us to take our studies from the grammar and dialectic stages into the rhetorical (or poetic) stage, which is much richer soil. For example, the poem, “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere,” is often studied as part of the history of the American Revolution, but the poem’s relationship to the American Revolution is only superficial. It was actually written just prior to the American Civil War. It was intended to be a call to arms for Americans in the North to embrace the effort to abolish slavery. Knowing this gives the poem much more passion and historical significance.

The ideas of history are difficult to wrestle with. We need to hear the voices of the people by integrating literature into the study of history, and we need opportunities to talk through the ideas with peers, parents, and tutors. This is not the dry history in textbooks that I studied. This is exciting, but it only happens when you can step out of the unit study and compare ideas throughout the timeline.

Several years ago, Oprah did a segment on why teens drop out of high school. She showed videos of teen dropouts explaining why they left. It sounded to me as though they were saying that they left because they were bored. My theory is that teens get bored when they are only doing grammar level work and their spirits long to progress to the rhetorical, poetic level where they can hear and discuss the big ideas. My own fifteen year old son is never more animated than when he is trying to explain to me a complex idea of a philosopher and what effects that might have on us. As parent-teachers, we may be timid about diving into this uncharted territory. We may feel that we have to know all the answers before we pose a question. That is a myth. Our high school students do not want us to merely give them facts in lectures. They want to engage with us in conversations about big ideas. They want to wrestle with them and discover them themselves. So, jump in with them. Compare ideas and brainstorm with them. There is no reason to hesitate. In the world of ideas, there is no right or wrong. There are superior ideas and there are inferior ideas. There are ideas that clash and some that have no relationship. It is the discussion between you and your student that matters, not a set answer. Although, if you compare each idea to the teaching of Jesus, you may discover the truth which could be considered the “right” answer, but this is not going to be on a multiple choice test at the end of the year. It will show in the formation of their hearts and minds. It will show in their response to current events and, eventually, in the quality of leadership they display.

The Classical Acts and Facts History Cards are foundational, but they are not just for Foundations students. They form the underlying (and sometimes hidden) spine for Challenge studies in literature, history, government, philosophy, art—well, everything! Build a house of truth and beauty with the firm foundation of history. Perhaps I will even sponsor a competition next year among the Challenge students in my CC community and reward those who can memorize the timeline. I could call it, “Are you smarter than a 6th grader?”