At Classical Conversations, we are always working to refine our language and intent with our words. We have updated this blog article to reflect these refinements so you can be equipped to homeschool your family with confidence.

What are the fifteen classical tools of learning? If you’re not in a Classical Conversations program yet and you’ve flipped through the catalog, you may have come across some unfamiliar terms like “the Five Core Habits of Grammar.” In this blog post, Challenge graduate Elise DeYoung explains these concepts and more.

Also, be sure to check out a speech on the 15 tools of learning in classical education delivered by Leigh Bortins, the founder of Classical Conversations, featured at the conclusion of this article!

Table of Contents

The Trivium and The Lost Tools of Learning

The 5 Common Topics of Dialectic

The 15 Tools of Learning and Classical Education

Video: 15 Tools to Help Your Child Learn Anything

The Trivium and The Lost Tools of Learning

The trivium is an ancient model of classical education that is centered around the study of grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric, in that order. At its peak during the Middle Ages, the trivium was widely accepted and extremely effective.

But today, this style of education is rarely used—and certainly not in public schools. Why?

Some, like Dorothy Sayers in her speech The Lost Tools of Learning, argue that we have fallen prey to a progressive education system that teaches isolated facts over vital skills. Unlike modern education, Sayers states that the “whole of the Trivium was in fact intended to teach the pupil the proper use of the tools of learning, before he began to apply them to ‘subjects’ at all” (Sayers, 7).

Today, this is a foreign concept. What do you mean the focus of education isn’t on learning subjects? Isn’t that its entire purpose? Yes . . . and no. Of course, education involves the reception of information, and information can come in the form of individual subjects.

But first and foremost, any worthwhile model of education must offer its students the tools of learning so that they are equipped to learn on their own. According to Sayers, the art of learning has been lost. And if we are being honest, I think we would have to agree. We must then ask ourselves the question: how do we get the art of learning back?

The solution is simple. We must return to the trivium.

The 5 Core Habits of Grammar

The first stage of the trivium is grammar.

Dorothy Sayers makes the argument that the grammar stage should take place while students are young because that is the age “in which learning by heart is easy and, on the whole, pleasurable” (Sayers, 10). The natural imagination and curiosity of children must be embraced and encouraged at this point in their development, and that is what the grammar stage is designed to do.

If I’ve learned anything from Classical Conversations, it’s that we must always carefully define our terms. So—what is grammar?

Grammar, in the modern sense of the word, is strictly the study of a language. In the Middle Ages, however, grammar claimed a much broader definition as the study of the language of any given topic: sports, geography, music, whatever. That’s why grammar was considered foundational.

Before you can play baseball, you must know what a baseball bat is.

Before you can travel to a country, you must know what a border is.

Before you can read sheet music, you must know what a quarter note is.

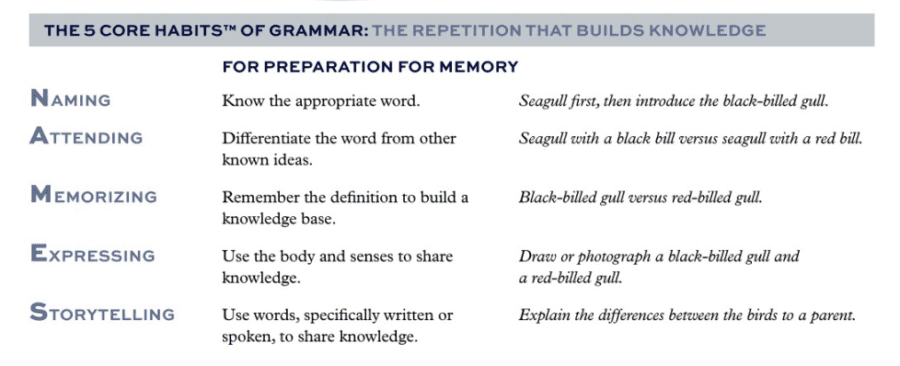

Without grammar, all learning is impossible. However, we cannot teach the grammar of everything, and so Classical Conversations has prepared the Five Core Habits of Grammar to teach students how to learn the grammar of anything. The habits are these:

- Naming: Know the appropriate word.

- Attending: Differentiate the word from other known ideas.

- Memorizing: Remember the definition to build a knowledge base.

- Expressing: Use the body and senses to share knowledge.

- Storytelling: Use words to share knowledge.

Learning the Foundations of Music with the 5 Core Habits of Grammar

I began taking piano lessons when I was very young.

When I first began playing, I really wasn’t concerned with learning the foundational theory of music. Honestly, I only wanted to stumble through those early years so that I could graduate to performing (what I deemed to be) “impressive” pieces of music. Simply put, I wanted to skip the grammar stage.

But again, I must emphasize that before you can read music, you must know what a quarter note is.

So, I had to take a step back and learn to name the notes. I learned about quarter notes, the bass clef, ledger lines, and so on.

This required a lot of attending on my part. Drilling and repetition were required for me to retain and recall the theory of music before I could put it to use.

Through attending to theory, the habit of memory began to display itself. By this time, whenever my teacher questioned me on a certain note value or asked for the definition of a time signature, I was able to give an accurate response. I had worked to commit these terms and their definitions to memory.

Soon, I was expressing these basic terms to my little sister as we sat side by side on the piano bench. Although limited at the time, my knowledge of theory was enough for me to explain the elements of a piece of music to others. Music is a written language that, like all other languages, must be learned before it can be used to communicate.

So, after I had begun to grasp the grammar of this language called music, I slowly began storytelling, using the symbols and definitions I’d studied. I learned simple songs that put my understanding of grammar to use, and soon, I was reading and playing music!

Grammar in Classical Conversations

What does this process of learning grammar look like in Classical Conversations?

In Classical Conversations, the grammar stage is fittingly referred to as the Foundations program. Designed for students ranging from ages 4 to 12, Foundations focuses on gathering and storing information for future use. Foundations students will learn the names of many things, ranging from Latin endings to historical figures. They will memorize these facts through songs and repetitions, and eventually, they will express them to others through presentations and group discussions.

One note: we must remember that the purpose of the Five Core Habits of Grammar is not application but rather retention. Or, as Dorothy Sayers put it, we must “look upon all these activities less as ‘subjects’ in themselves than as a gathering together of material for use in the next part of the Trivium” (Sayers, 13). This next phase of the trivium is dialectic.

The 5 Common Topics of Dialectic

The dialectic phase of the trivium is focused on teaching students to analyze new ideas and is centered around logic, which is “the art of arguing correctly” (Sayers, 14).

As students mature in their thinking, they will naturally begin to critically process material gathered during the grammar stage and decipher the truth (or lack of truth) in what they have learned.

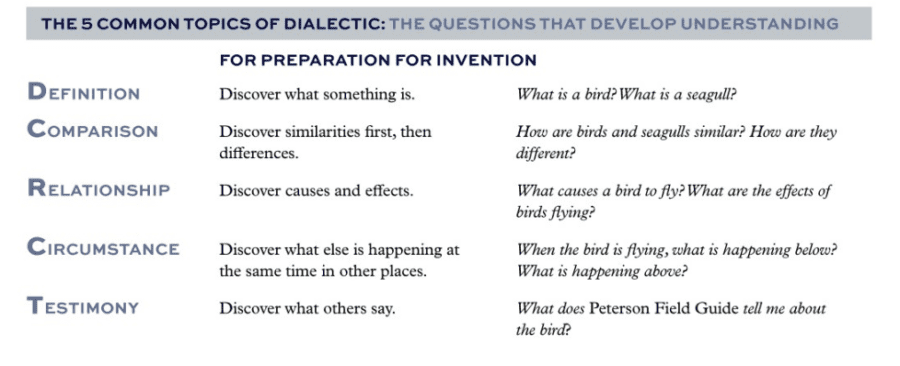

They begin searching for the “why” and “how” rather than simply the “what.” The tools CC teaches to help guide students through this delicate process are the 5 Common Topics of Dialectic:

- Definition: Discover what something is.

- Comparison: Discover similarities first, then differences.

- Relationship: Discover causes and effects.

- Circumstance: Discover what else is happening at the same time in other places.

- Testimony: Discover what others say.

Mastering the Essentials of Music with the 5 Common Topics of Dialectic

Now that I could read simple music scores and play along, I once more desired to play those “impressive” songs, and so I began experimenting with music I’d find online and print out for myself.

In this more complex music, however, there were often notes and rhythms with which I was completely unfamiliar (what is a triplet, anyway?). I quickly realized that if I wanted to advance in my piano playing, there were more complex definitions I had to learn. Thankfully, I had a foundation in the Five Core Habits of Grammar, so I resorted to those as I defined the new terms I encountered.

During my lessons, when presenting me with a new piece of music, the question my teacher always asked me was, “What do you see?” Often, my responses sounded something like “This measure is like this other one,” or “This rhythm is different than the one preceding it,” or “Oh boy, that looks complicated . . . ” This process of comparison is very valuable when faced with a new task, or in my case, a new music score.

A few years ago, I began to play piano for the high school worship team at my church. This meant I had to master playing chords and changing keys. I was able to easily learn how to play a song based solely on chords through the skills of memory and comparison I had previously established. But changing keys was an entirely new mountain I had to climb. If a piece of music was in the key of D, and I was asked to change it to the key of G, what would happen? How would the sharps and flats change based on the key that was chosen? These questions of cause and effect taught me to identify the relationships in music.

The most important, and most obvious, requirement when playing in a band is understanding how other instruments work and what their role is in music. When tackling a song, I had to know what tempo the drums would set, what rhythm the guitar would play, and the key the vocalists would sing in. All these circumstances required me to analyze the music and the band in order to give my best performance.

During worship practice, I had the privilege of learning from other musicians who would come to help instruct and guide us. They taught us how to improv introductions and endings to songs, adapt songs to fit our capabilities and resources, and, most importantly, how to honor God through music. By listening intently to their testimonies, I better grasped how to compliment other band members with my playing and grew significantly in my musical knowledge and capabilities.

Dialectic in Classical Conversations

I have stated already that the dialectic stage is focused on logic and reasoning. So, during this time, students will be introduced to formal logic, apologetics, and the Socratic Dialogue. And alongside logic, the dialectic stage begins to teach students how to communicate sound ideas through writing.

This process begins during the Essentials program and extends through the lower Challenge levels—namely, A, B, I, and II—encompassing, broadly, ages 12 to 14. Analyzing and arranging material gathered from the grammar stage and beyond is a pivotal activity in a child’s education.

With the ability to process new ideas securely established through the Five Common Topics of Dialectic, students will find great success as they continue to learn in and outside of the classroom.

The 5 Canons of Rhetoric

As noted by Leigh Bortins in her book The Conversation, rhetoric is “the use of knowledge and understanding to perceive wisdom, pursue virtue, and proclaim truth.”

This final stage of the trivium is intended to teach students how to proclaim truth through communicating what they have learned. At this stage of the trivium, students will have learned how to process and analyze information, and now they will naturally begin to form their own opinions.

But what use are their opinions to them if they do not know how to express them in a clear and persuasive manner? This is why we need rhetoric.

Historical men such as Cicero and fictional men such as Mark Antony from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar are examples of men who mastered rhetoric. This branch of the trivium is oftentimes the most popular because it displays a student’s knowledge and skills in an artful and impressive manner.

Whether addressing Congress, leading a Bible study, or holding a dialogue with a friend, it is extremely important that we each have the skills to express and persuade well.

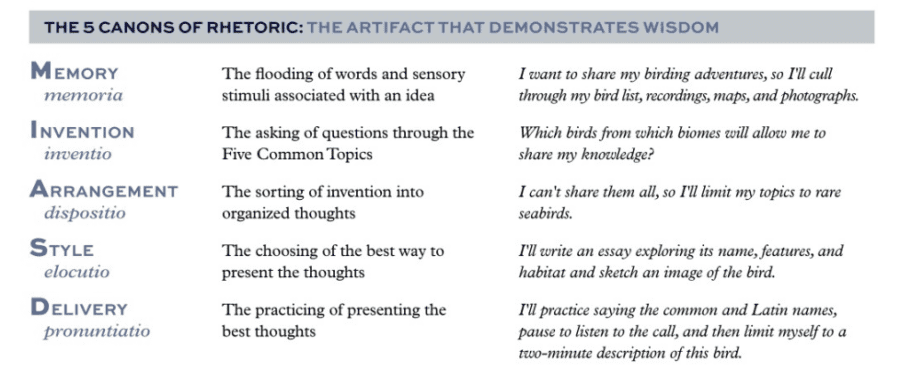

In order to help students attain these skills, CC makes use of the medieval model of rhetoric, known as the Five Canons of Rhetoric:

- Memory: The flooding of words and sensory stimuli associated with an idea.

- Invention: The asking of questions through the Five Common Topics.

- Arrangement: The sorting of invention into organized thoughts.

- Style: The choosing of the best way to present the thoughts.

- Delivery: The practicing of presenting the best thoughts.

Embracing the Challenge of Music with the 5 Canons of Rhetoric

Composing music is no small feat. It takes a high level of musical knowledge, skill, and imagination to speak (or rather play) a song into existence.

I learned this when I first began to sit down at the piano and try to write my own song. Often, I found myself discontented because the music never seemed to come out how I wanted.

This always puzzled me. I’d been playing piano for so long! Why was I seemingly incapable of writing a few measures worth of music? It wasn’t until later that I realized, once more, I had been skipping the necessary first steps of composing and just expected a song to come from the keys.

When composing anything, whether it be a speech or a song, you must start from nothing—a blank page or a quiet room—and a step-by-step process to help spark and foster the creative process.

If you are a musician, you know there will come a time when someone asks you to play. For you, this may feel like the kickoff of Armageddon, or it could be your invitation to Paradise. My feelings over such a question are normally dependent upon my level of preparedness—do I have a song memorized? Whether it is an original composition or your favorite classical piece, you may be asked to play without access to your music score, so memorization is a key aspect of performing. Memorization also elevates your performance, so whether you are playing at a recital or family gathering, you will always be prepared to deliver your song well. Thankfully, the habits of grammar equip us to memorize anything, including music, with ease.

The invention of a song is a crucial process that requires you, as the composer, to decide what story you want to tell through music. (Remember storytelling in the grammar stage?) Do you want your song to be fast or slow? Major or minor? Long or short? These questions, and many others, can be answered using the 5 Common Topics of Dialectic and will help you produce and process new ideas.

Abstract ideas for a song, however, are not helpful unless they are arranged properly. Notes must be confined to measures in order for choruses, verses, and bridges to be formed. Arrangement is a tedious process of writing, revising, and rearranging, but it is absolutely necessary if you wish to produce something other than a cacophony.

Once you have your melody, it is time to make it musical. Adding dress-ups such as crescendos, tempo dynamics, and key changes brings elocution (or style) to your piece. You will engage your audience through your entire piece and elevate it from a catchy tune to an impressive composition.

Finally, whether you are penning or just playing a piece of music, you must decide how you will perform the piece. The delivery of a song is just as important as the invention of it. You can make Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata sound unpleasant if you play it poorly—believe me, I have. Style, mood, pace, and emotion are all essential aspects of a good performance.

With this final step, you will be prepared to give your best performance and communicate well through the keys.

Rhetoric in Classical Conversations

Rhetoric is first introduced to students in CC when they begin presentations in Foundations.

However, it’s not until the later Challenge levels, specifically III and IV, that rhetoric is taught with the goal of mastery in mind. Dramatic interpretations, memorized expository addresses, and the Senior Thesis project all teach students to master the Five Canons of Rhetoric and apply them when communicating under a variety of circumstances.

Did you know that Cicero first laid out the Five Canons of Rhetoric in De Inventione?

The 15 Tools of Learning and Classical Education

Do you ever find that young people, when they have left school, not only forget most of what they have learnt (that is only to be expected) but forget also, or betray that they have never really known how to tackle a new subject for themselves? . . . The intellectual skills bestowed upon us by our education are not readily transferable to subjects other than those in which we acquired them . . . [students] learn everything, except the art of learning – Dorothy Sayers

In modern education, the art of learning has been lost and replaced by a mindless regurgitation of facts. We need to recover the lost art of learning because learning is not limited to the classroom. Rather, education is a lifelong venture that we must prepare for.

The classical model for education is intentionally designed to foster the skills of memory, reason, and communication through the trivium so that students are equipped to leave their childhood and adolescence as lifelong learners.

With such a lofty educational goal, it’s imperative that we take advantage of the fifteen tools of learning that the trivium provides. The Five Habits of Grammar, the Five Common Topics of Dialectic, and the Five Canons of Rhetoric are fifteen practical tools of learning that will train you and your student to retain, analyze, and communicate ideas well.

You may feel like you are drowning in grammar and logic and quarter notes. Maybe you are worried that it is too late to learn how to swim. But I have good news! These tools can be taught at any time and can be used during all stages of life.

If you have been homeschooling your students for years and are just now learning about these habits, you’re not too late!

If you can’t homeschool but still want your children to possess these tools, they can!

If you have already graduated from high school and college and want to grow in these skills, now is the time to start!

Education is a lifelong pursuit that we can all prepare for. As you seek to implement these learning tools in your home, just remember one thing:

Before you can read music, you must know what a quarter note is.

If you’d like to learn more about the 15 tools of learning in classical education, be sure to check out this speech by CC founder Leigh Bortins from the 2023 HEAV Annual Convention.