The classical education movement is gaining momentum.

Let’s start with some numbers. According to a market analysis conducted by Arcadia Education in 2024, over 677,500 students were enrolled in classical schools nationwide during the 2023-2024 school year (and this number includes homeschoolers following a classical curriculum). The analysis also predicts a sustained surge in classical education, with enrollment projected to reach 1.4 million students by 2035—more than doubling current figures. Meanwhile, according to research by Brookings, public schools have taken a beating as 12 percent of elementary schools and 9 percent of middle schools have experienced a 20 percent drop in enrollment since COVID-19.

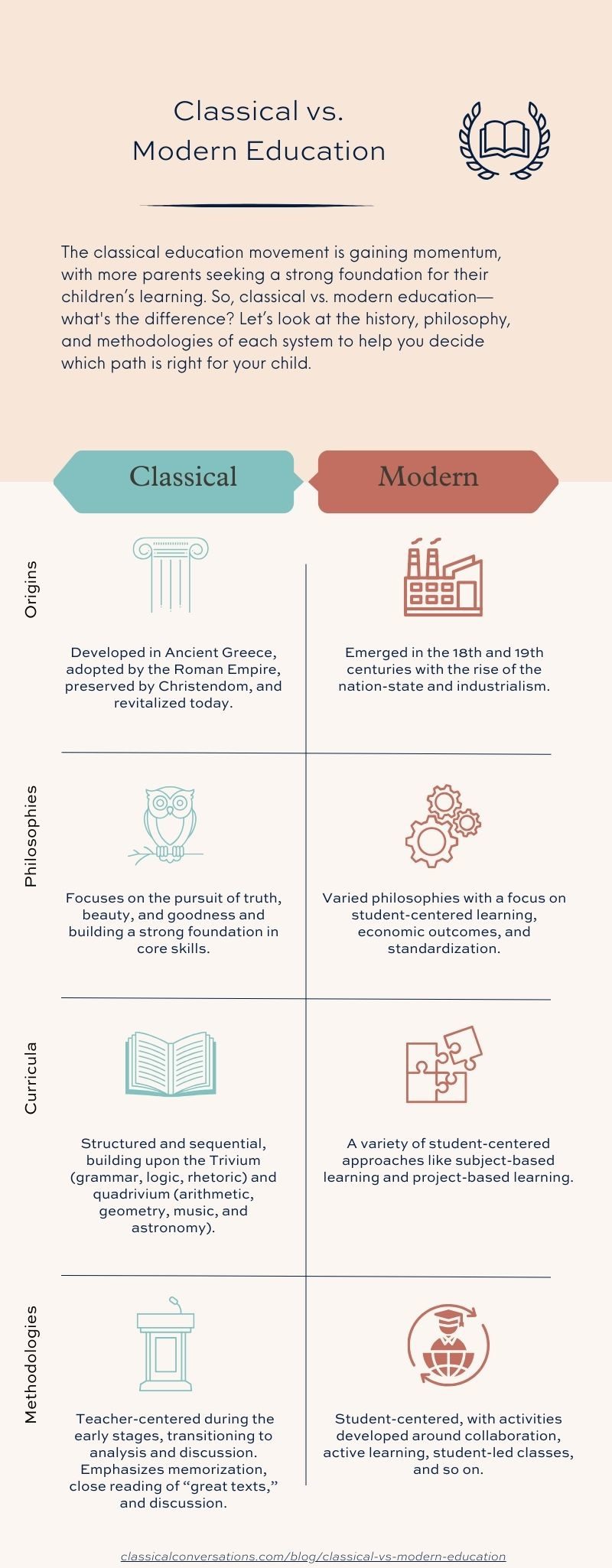

Change is on the horizon. Parents will have more options for educating their children than ever before. This may lead many to wonder: classical vs. modern education—what’s the difference?

In this blog post, we’ll look at the history, philosophy, and methodology of each approach to education, and then we’ll turn our attention to the question of which approach is better. If you’d like the tl;dr, skip ahead to the comparison chart.

I. What Is Classical Education?

History

Our story begins in the Greco-Roman world. In the democratic polis (or city-state) of classical Athens, education was seen as crucial for shaping virtuous leaders and active participants in civic government. Thinkers like Socrates, the father of Western philosophy, emphasized the importance of questioning and dialogue in the pursuit of truth. His student, Plato, envisioned an ideal education system focused on developing the mind to instill a strong sense of civic virtue in the student. Building upon these ideas, Aristotle, known by later generations as The Philosopher, further developed this theory of education and refined some of the key terms of classical education, terms like grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric.

The Roman Empire, with its emphasis on law, order, and oration, readily adopted the Greek model. Roman educators incorporated their own values into this system, centering upon family and home as the locus of learning rather than the academy and emphasizing practical skills. Like the Greeks across the Ionian Sea, the Romans believed education should prepare students for a life of civic virtue (or pietas).

After the decline of the Roman Empire in the west and the subsequent collapse of secular education, classical education found a safe haven in Christian monasteries, where monks preserved ancient texts to ensure the survival of classical knowledge. These monks ran cathedral schools and monastic schools where they applied the classical method of education in teaching children. Thus, Christendom inherited the wisdom of antiquity, and in turn, classical education became synonymous with Christian education.

As we’ll see when we turn our attention to modern education, the classical model of education was the standard model until the modern period, when education was reenvisioned and repurposed first as a means “to build national identities” and then as a means for “economic development in Great Britain and across Europe and the United States before and during the Industrial Revolution.”

But our story doesn’t end with the disappearance of classical education. The 20th century witnessed a renewed interest in this timeless model. Pioneers like Dorothy Sayers, a renowned British mystery writer, and Leigh Bortins, an American educator, spearheaded this movement. Sayers, in her influential essay “The Lost Tools of Learning,” argued for a return to the core principles of classical education, emphasizing the importance of logic, clear thinking, and the study of great literature. Inspired by Sayers, Leigh Bortins and other leaders in the classical education movement have revitalized classical education (which brings us back to those numbers presented at the beginning of this post).

Philosophy

To quote Andrew Kern, founder of the CiRCE Institute: “Education is the cultivation of wisdom and virtue, and it is accomplished by nourishing the soul on truth, goodness, and beauty.”

This is the heart of classical education.

The classical model of education rests on a core philosophy that emphasizes the pursuit of truth—universal and timeless truths that transcend generations and cultures. This philosophy translates into a structured curriculum designed to cultivate wise and virtuous individuals.

The classical curriculum is often divided into two categories of learning: the trivium and the quadrivium.

The trivium, meaning “the three ways” in Latin, forms the foundational This arts focuses on mastering the fundamental tools of language and thought:

Grammar: This is not merely about memorizing sentence structures. Yes, classical grammar delves into the mechanics of language, analyzing word parts, sentence construction, and the logical relationships between words and ideas, but ultimately, grammar involves the accumulation of knowledge through memorization of the rudimentary facts of any subject.

Dialectic: Moving beyond the, dialectic focuses on the art of reasoned discourse. Students learn to analyze arguments, identify logical fallacies, and construct arguments of their own. This skill is essential for navigating complex ideas, evaluating information critically, and engaging in meaningful dialogue.

Rhetoric: Having mastered the tools of language and reasoning, students move on to rhetoric reasoning, the art of effective communication. They learn to use language persuasively and elegantly, tailoring their arguments to different audiences. To quote Leigh Bortins: “An educated person is not someone who knows something, but someone who can explain what they know to others” (The Core, Chapter Four).

Once a strong foundation is established in the trivium, students progress to the quadrivium, meaning “the four ways.” This arts focuses on the mathematical and scientific disciplines:

Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, and Astronomy: The quadrivium emphasizes understanding the underlying principles and relationships within each discipline. Through these subjects, students cultivate a sense of order and beauty in the world and hone their ability to reason through abstractions.

The trivium and quadrivium work together to guide students toward the goal of education: to know God, to love Him, to imitate Him, to be like him. Furthermore, by mastering the classical skills of learning, students are empowered to grapple with the great ideas that have challenged humanity for centuries. They learn to analyze complex texts, identify flawed arguments, and formulate their own conclusions. This emphasis on eternal truth ensures that classical education equips students not just with the skills to succeed in the here and now but also with the intellectual foundation to navigate the ever-changing world around them.

Methodology

Classical education employs a specific methodology that’s aimed at fostering a love of learning and equipping students with the tools to become lifelong learners. Or, to quote Leigh Bortins once more, “The classical approach trains the student to become a thorough and capable learner, rather than focusing on training for a single job skill.” This methodology can be broadly categorized into three key arts of learning that mirror the trivium:

1. The Art of Grammar

Emphasis on Memorization: We have a natural ability to absorb large volumes of information through repetition. (Just look at how quickly toddlers pick up their native language!) Classical education capitalizes on this by employing techniques like recitation, songs, and chants to instill grammar skills and teach acts, historical timelines, and even classical poems or mottos. This creates a strong foundation of knowledge upon which future learning can build.

‘The foundation of a classical education begins with parents teaching children the art of memorization and grammar studies. Some educators might dismiss rote memorization, but I argue that it is beneficial because it trains your brain to hold information. It is the most organic way of learning ever devised and goes hand in hand with the way we naturally relate to our children.’ —Leigh Bortins, The Core, Chapter One

Direct Instruction: Teachers provide direct instruction to students. Direct instruction is a teacher-directed method that uses explicit techniques to teach skills (in this case, the art of grammar). That’s not to say that the student’s needs aren’t considered, but the emphasis is on the impartation of foundational knowledge.

2. The Art of Dialectic

Emphasis on Analysis and Discussion: Students’ natural curiosity and questioning nature come to the fore. The classical methodology caters to this by transitioning from direct instruction to more open-ended discussions and Socratic questioning. Teachers guide students to analyze texts, identify logical fallacies, and engage in respectful debate. This fosters critical thinking skills and the ability to think independently.

Close Reading of Great Texts: Classical education prioritizes the study of “great texts”—enduring works of literature, philosophy, history, and science. Students engage in close reading, dissecting the meaning, purpose, and historical context of these works. This exposure to timeless ideas broadens their worldview and develops their analytical skills.

3. The Art of Rhetoric

Emphasis on Communication and Persuasion: Having honed their critical thinking and analytical skills, students using the art of rhetoric learn to communicate their ideas effectively. They explore different writing styles, practice persuasive arguments, and develop public speaking skills. This empowers them to not only think clearly but also to share their knowledge and perspectives with confidence.

The Importance of the Arts and Literature

The classical methodology recognizes the importance of the arts and literature in forging the well-rounded person. Music, drama, and visual arts are integrated into the curriculum, fostering creativity, imagination, and an appreciation for beauty. Additionally, the study of classical mythology, literature, and history not only provides historical context but also allows students to explore timeless themes and grapple with enduring human questions.

Now, let’s turn our attention to modern education.

II. What Is Modern Education?

History

Modern education, unlike its classical counterpart, has a shorter and more turbulant history with roots that can be traced back to the 18th and 19th centuries, a period marked by significant societal shifts, which in turn led to an explosion of competing educational philosophies.

The Industrial Revolution ushered in a new era where literacy and basic skills became essential for a growing workforce. Early forms of modern education emerged, focusing on basic literacy, numeracy, and practical skills needed for factory work. Tradition and character education fell by the wayside.

The rise of industrial nation-states and the ideal of an informed citizenry further fueled the need for public education systems. Governments across Europe and North America began establishing taxpayer-funded schools to educate the masses. These schools aimed to provide a standardized curriculum and instill basic skills and largely secular values in children.

‘I am criticizing the professionalization of teaching children because these young human beings are not cogs in a machine, And I am trying to identify the root of the problem for all those wonderful adults who went into teaching thinking that they could commit to nurturing the lives of many children only to end up having the system squash their excellent motives. Our current school system replicates factories and requires classroom managers more than teachers. Teachers are appreciably frustrated.’ —Leigh Bortins, The Core, Chapter One

The 20th century saw a major shift in educational philosophy with the rise of progressive education. Men like John Dewey challenged the teacher-centered approach of the traditional model of education and advocated for student-centered learning. Progressives focused on the atomized individual—the child apart from family, apart from community, apart from history. In theory, progressives aimed to instruct students using active learning experiences. Project-based learning, hands-on activities, and a focus on social and emotional development became the battle cries of this movement.

Despite a promising start, the results were disastrous, which is why the latter half of the 20th century saw a growing emphasis on standardized testing and accountability in education. These measures aimed to ensure that all students were meeting certain academic benchmarks. While proponents argued that standardized testing provided valuable data for tracking student progress, identifying areas for improvement, and holding teachers accountable, critics argued that it narrowed the curriculum and stifled creativity. This movement toward standardization led to the even more disastrous Common Core.

Today, modern education continues to grapple with the internal contradictions posed by its philosophies. Modern philosophies of education all place the individual at the center of the universe, but that commitment to individualism apparently requires state intervention—aka, collectivism—to maintain. Any philosophy that’s marked by incoherency is a doomed philosophy. This tension will need to be resolved if the modern approach is to survive the 21st century. (Don’t hold your breath!)

Philosophy

Unlike classical education, modern education isn’t unified by one coherent philosophy but instead consists of numerous competing philosophies that bear a “family resemblance,” to borrow a term from the philosopher Wittgenstein. (These philosophies include progressivism, as mentioned above, radicalism, essentialism, democratic education, and more.) These ideologies share overlapping similarities, including a vested interest in students’ contributions to their society’s social and economic activities in adulthood, as well as:

Focus on the Individual Learner: Modern education emphasizes the unique needs, learning styles, and interests of the individual student. Of course, there’s an unresolved tension in this particular focus, which we noted above and will address again below.

Mentorship and Coaching: Direct instruction is out—even for the youngest learners in modern schools. Students, not teachers, are the focal point of modern education, and that means teachers are relegated to the role of mentor, coach, guide, and positive role model. Now, the classical teacher also shares these different roles, but only when the student has mastered the art of learning (generally, rhetoric).

Active Learning and Student Engagement: Modern classrooms encourage students to be active participants in their own learning. The focus shifts away from memorization, lectures, and Socratic circles to hands-on activities, project-based learning, and collaborative discussions. The underlying belief here is that active learning prepares students for the “real world” (i.e., economic activities).

Standardization and Differentiation: This is another point of tension in modern education. There have been two trends pulling in opposite directions: standardization and differentiation. The first, standardization, involves a movement towards a single, centralized, bureaucratic educational standard and comes from a place of concern over accountability and the technocratic preoccupation with data. The second, differentiation, stems from an individualistic worldview and involves the custom tailoring of curriculum, materials, methods, and so forth to the individual learner. These two foci are at odds with one another, and so some modern philosophies favor one over the other, while others, like progressivism, try their hardest to reconcile them.

Methodology

Modern education’s diverse philosophies translate into a variety of methodologies designed to cater to individual learning styles and the needs of the state. Here’s a breakdown of some popular methods used in modern classrooms (and we’ll note the classical perspective for each):

Subject-Based Learning

This approach organizes learning around core subjects like math, science, history, and language arts. Although subject-based learning tends to approach subjects in isolation, there’s been a conscious trend toward forming interdisciplinary connections across topics in recent years. For example, a science unit on the solar system could be combined with a language arts project on writing space-themed narratives.

(The classical model neatly sidesteps this issue by focusing on skills rather than subjects.)

Student-Generated Assignments (SGC)

This methodology encourages students to take ownership of their learning by actively creating content. This can take many forms, such as creating presentations, writing blogs, developing multimedia projects, or participating in online discussions. SGC is intended to foster critical thinking, communication skills, and collaboration as students research, analyze information, and present their findings.

(Classical educators would note that this technique puts the horse way, way, way out in front of the cart when employed too early in the student’s life. Students must learn how to walk before they can run. However, this would be an entirely appropriate method at the rhetorical art of learning.)

Immersion and Project-Based Learning (PBL)

These approaches share a common thread: they are intended to propel students into engaging, real-world experiences. Immersion programs might involve language students living abroad or engaging in virtual reality to “explore” historical periods. PBL, on the other hand, tasks students with tackling open-ended projects that require them to apply their knowledge and skills to solve a specific problem or answer a question. At their best, both methods encourage active participation, collaboration, and the development of essential life skills like research, problem-solving, and critical thinking.

(Again, classical educators will employ these methods at the dialectical and rhetorical arts of learning but would strongly disagree with their use when immersed in the art of grammar.)

STEM/STEAM

In keeping with modern education’s industrial roots and economic motivations, there’s been a growing emphasis on STEM/STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, [Arts], Mathematics). Students are meant to gain a deeper understanding of how these subjects interrelate to solve so-called real-world problems. For example, a STEM project might involve students designing and building a model bridge, incorporating scientific principles, engineering design, and potentially artistic elements into their creation.

(Again, the ever-quotable Leigh has this to say about STEM/STEAM in Chapter Three of The Core: “As much as I love technology and think it has value in education, most real learning comes from wrestling with big ideas and arguing with another person. New technologies force us to anticipate all the exciting changes we can imagine in a different world, but they also can rob us of the relationship between a student and his mentors.”)

III. Classical vs Modern Education: A Comparison Chart

IV. What Is the Right Approach for Your Child?

Before we answer this question, let’s address the elephant in the room. If you’re a Westerner, you live in a highly individualistic and, therefore, relativistic culture. You’ve probably heard people say that there’s no best approach—you should consider your child’s learning styles and educational goals.

Boo, we say! Boo!

While modern education espouses relativism, classical education does not, and that leaves us with only two answers to the above question: either classical education is the right approach for your child, or there is no right approach for your child—every approach is equally valid.

We can apply a modified version of Pascal’s wager here. This thought experiment asks you to weigh the potential benefits and drawbacks of two choices.

In this case, let’s compare the claims of classical vs. modern education:

Choice A: Classical Education. Classical education is the right approach for every child because the model comes from a place of universal truth. Any educational model that does not acknowledge universal truth will yield inferior results because that model denies the very basis for the exchange of knowledge—basic facts and universal constants.

Choice B: Modern Education. The best approach is the student-centered approach, which will change according to the student. Education is subjective, not objective. Therefore, there is no “best” approach. Whatever works for the student works.

If you were to wager on those two options, classical education would be a much safer bet. If the classical model is right, you’ve landed on the model that values truth and the right way of learning. And if the modern model’s premise is right, well, it doesn’t matter—the classical model could still work for you! Either way, you win.

So, classical vs modern education—which should you choose?

The stakes are high. Classical education offers a time-tested and time-proven path, one that has nurtured brilliant minds for centuries. Modern education presents a variety of options, some effective under the right circumstances, some less so.

The choice is yours. But before you decide, we encourage you to dive deeper into classical education. Discover how it can ignite your child’s curiosity, equip them with timeless skills, and shape their character for the better. The Core by Leigh Bortins—which we’ve quoted pretty extensively here—would be a great place to start!

Remember, a strong foundation is the key to building a magnificent structure. Classical education provides that foundation—a strong foundation built upon the enduring truths that have shaped civilizations for generations.