The mythos represents man’s imaginative and, ultimately, spiritual effort to make this world intelligible; the logos sets forth his rational attempt to do the same.1

Humans have two basic tools with which to make this world intelligible: the mythos and the logos; anything else results in incoherence and a rejection of order and purpose. The former, as explained above, is an imaginative and spiritual understanding of this world; the latter is a logical and rational understanding of this world. Error comes when one forces a decision of one over the other; error arises when, as Stratford Caldecott describes in Beauty for Truth’s Sake, one divorces truth from beauty or beauty from truth, and elects one without the other.2

Unfortunately, we often find ourselves—consciously or not—choosing one over the other. The mythos, remember, is an imaginative and spiritual intelligibility, or a means of understanding life and the world. We find the mythos expressed and communicated to us in many ways. Primarily, we discover it in stories. Take, for example, The Chronicles of Narnia. In it, truths are communicated beautifully to the reader about heroism, honor, duty, truth, faith, love, friendship, loyalty, honesty, and a host of other virtues. The author does not analytically define friendship and expect his reader to live it out. Rather, he displays friendship in his characters, and the reader wants to imitate Lucy and Mr. Tumnus and have that kind of a friendship in her own life. Neither does he analytically define heroism, yet the reader wants to imitate the heroism and valor of Reepicheep.

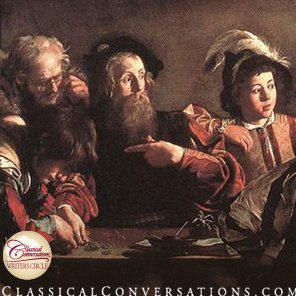

The mythos, however, is not only expressed in stories with words. Paintings communicate a similar intelligibility of the world, precisely because they are telling a story, though it is a story without the use of words. Reflect on Caravaggio’s The Calling of St. Matthew. In The Calling, you see the timeless message of Christ calling His people. You see the timeless responses of people of all ages eager, confused, bored, bothered, and bewildered. The Christian sees himself in any one of those characters, responding in each of those ways at different times in his life. The mythos also communicates the same intelligibility through music, with or without words.

The church can be a good example of this division, this emphasis of mythos over logos or vice versa. Many have experienced churches in which the primary emphasis is on beauty at the expense of truth. The liturgy, architecture, and aesthetics of worship are not just beautiful, but they communicate a mythos to the participants. The height and point of the spires and ceiling direct us upward, away from us, and toward God. The order of the liturgy calls us to worship, to remember our sin, to repent of our sin, to trust God for forgiveness, to be spoken to through the Word, to be nourished in the Supper, and to be commissioned to return to the world prepared for spiritual battle. When these churches exclude the logos, however, the worshipers lose the logical and rational understanding that is also so important in making this world intelligible.

On the other hand, many have experienced churches in which the primary emphasis is on truth to the exclusion of beauty. The liturgy, architecture, and aesthetics of worship convey no additional meaning, or—worse—they communicate that beauty is unimportant and insufficient. Yet the Bible teaches exactly the opposite: the beauty of creation explicitly communicates not just the glory of the Lord, but also His divine attributes! Thus, these churches seek to communicate the intelligibility of this world only through rational means, the logos, when God himself communicates through both.

If the intent of the church is imitation of the God who communicates through both mythos and logos, His church should communicate through both—knowingly and intentionally. The reading of Scripture and the preaching of His Word communicate the logos—most clearly—to the participant. The liturgy, architecture, and aesthetics of worship communicate the mythos—most clearly—to the participant.

As it is in worship, so should it be in life. We learn through mythos and logos; we should teach through mythos and logos. We should immerse ourselves and our children in the beauty, truth, and goodness of stories, art, music, and liturgy. Francis Schaeffer ordered his home at L’Abri with this end in mind. L’Abri was an environment intended to enable those in search of truth to find it, but to find it embraced by goodness and beauty. His home was decorated carefully and intentionally—even to the smallest detail of a flower arrangement on the dining room table—to communicate goodness and truth in its appearance and aroma. As seekers of truth came to discuss the logos they found themselves immersed in a visual, aural, and olfactory mythos.

There are three ways we often divide logos from mythos. While we may favor one over the other—because of our own interests, talents, or gifts—we must be careful not to impose this upon others. We may, furthermore, convince ourselves that one is easier to learn—by which we mean easier for us to learn in order to be able to teach others—and we will temporarily focus on it until we can learn the other. This, too, we must be careful to avoid. We are created in the whole image of God, not in a partial image. We should neither develop a partial image in ourselves, nor emphasize the development of a partial image in others. Finally, we may convince ourselves that those we are teaching are in more desperate need of learning one over the other. Yet, we must be careful to avoid such assumptions.

A brief consideration of this last point is important. Often, we tend to assert that people need logos more than they need mythos. First, let us consider the world in which we live. It is decidedly a postmodern world. This frustrates Christians who have a biblical worldview because of the rejection of absolute truth. Our response is to attack that view rationally with the logos. Postmoderns, however, by their very definition of truth are more likely to learn through the mythos. Because of their definition, it is not truth that moves them, but rather what is real that moves them. The things that are real are the truths which, experientially, affect and change people for the better or at least toward a desired end—whatever that may be. It is therefore the mythos that is more powerful for postmoderns—which may explain the deep desire in Americans for the ancient and authentic (both things which carry with them a story, a mythos.)

Second, let us consider the revelation we have received from God himself. The vast majority of revelation is what we theologically call general revelation, the creation. General revelation is always and only a mythos-type understanding of this world. A minority of revelation is what we theologically call special revelation. Special revelation is God speaking to us through prophets, Jesus, and other spokespeople, but primarily—today—through the written word, the Bible. A cursory glance of the Bible, however, reveals that it too primarily offers a mythos-type understanding of this world.

Do not misunderstand mythos here as make-believe, like the Greek and Romans myths of history. Mythos must still be understood as simply an imaginative and spiritual effort to make the world intelligible. The Bible, through story, offers us an imaginative and spiritual intelligibility of the world. That is not to say there are not logos aspects of the Bible. The Ten Commandments, for example, are a propositional, logos-centered presentation of truth. The vast majority of the Bible, however, is story. Its intelligibility is through mythos.

For these two reasons, if no other, we need to immerse ourselves in a world of mythos and logos, a world of imagination and logic, a world of truth, goodness, and beauty. For as truth is worth it for its own sake, so, too, is beauty worth it for its own sake. And, beauty is necessary for its own sake.