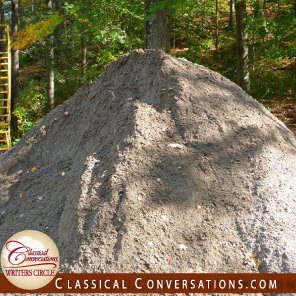

It started with a dirt hill. The large, unassuming pile of fill dirt occupied the back corner of our church property. To us adults it represented the unfinished nature of our construction efforts. To our children, it represented adventure, strategy, and conquest. Every Sunday after our worship service the hill would swarm with kids seeking alliances, plotting “takeovers,” and planning new battle strategies. We saw red mud that would stain our new floors. They saw a castle, a fort, or a “war zone.”

When one little girl overheard the grownups discussing the dismantling of the hill, she went into action. “We don’t want it moved,” she assertively declared. “Why can’t you tell them to leave it for us?” Her father, the pastor, was “disinclined to acquiesce to her request.” He suggested she approach the construction supervisor, if it meant that much to her. So, she went home and crafted a plan. She needed to show that the hill mattered to someone, so she persuaded her friends to sign a petition. Her daddy had told her she needed to give the grownups a reason to let the hill stay. Therefore, she drafted a speech on why the children cared about the hill, why it benefited the grownups to let it stay, and how the children would act responsibly if their request was honored. The next Sunday, she presented her petition and her argument to the man in charge. Clearly taken aback, and perhaps struck with admiration for her clear thinking and determination, he agreed to let the dirt hill stay.

Years later, I recognized in this story one of my daughter’s earliest examples of the art of rhetoric. She chose a position. She identified her audience. She pondered what would persuade that audience to come to her conclusion. She carefully couched the argument in words and reasons most likely to move her audience. She confidently presented her argument. She carried the day!

I am a believer that our students can begin to cultivate the skills of rhetoric early on. And it all started with a dirt hill!