I recently asked my mom, a longtime Challenge tutor, what she planned to do with her summer, teasing that she would be at a loss for what to do once her students were gone. She replied that she thought summer leisure time was a myth, adding, “The time always gets eaten up by other activities.” What an image! I could not help but envision a great green Busy Monster with garden trowels for hands and dirty plates for eyes. In my imagination, he was wearing a beach towel for a toga, a camp counselor’s lanyard, and a pair of paint-splattered sandals. The Busy Monster would go around finding a spare day on the calendar or a spare hour in the itinerary and gulping it down like a juicy wedge of watermelon. Anyone found to be idle would be startled into motion like a reluctant sheep.

The literature lover in me felt intuitively that Shakespeare would approve of my Busy Monster. He did, after all, coin the phrase “green-eyed monster” in reference to jealousy, and, furthermore, his characters knew the fear of being perennially active.

In Henry IV, part 2, Shakespeare’s roguish character Falstaff exclaims to the Lord Chief Justice, “I were better to be eaten to death with a rust than to be scoured to nothing with perpetual motion” (act I, scene 2). Now, I am not saying that Falstaff is an exemplar of industriousness or work ethic (far from it: he lives to eat, drink, and be merry, as the saying goes), but his statement does invite further thought about what it means to live in perpetual motion, whether in early modern England or in the present-day United States.

You see, when Henry IV appeared in English playhouses between 1596 and 1599, Europe was in the midst of a Renaissance not only of art and theatre, but also of exploration, invention, and engineering. In the world of invention, perpetual motion was pursued only a little less hotly than the fabled Fountain of Youth or the philosopher’s stone.

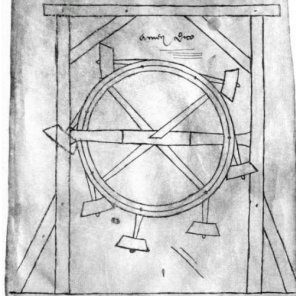

Less than ten years after Shakespeare’s play was written, in 1607, a Dutch engineer named Cornelius Drebbel would dedicate his “perpetuum motion machine” to King James I of England. He was not alone. Bavarians, Indians, Frenchmen, and Italians—including the great Leonardo da Vinci—had been playing with designs for perpetual motion machines since the eighth century A.D. The machines these men devised ranged from self-moving wheels and self-blowing windmills to overbalancing weights and water wheels. They used weights, magnets, water, or mercury to produce and recycle energy. Somehow, every one of these efforts ultimately failed.

Only later, in the nineteenth century, would scientists formulate the First Law and Second Law of Thermodynamics to explain why perpetual motion machines were doomed to fail. The concept of entropy, in particular, meant that energy could not be recycled continuously without the input of additional energy to counteract friction and other energy-depleting factors.

By now, you may be wondering, justly, what this long explication of perpetual motion has to do with the Busy Monster. To answer, I want to draw your attention to one key fact that the inventors of perpetual motion machines failed to realize: perpetual motion is only possible in a vacuum. In order for perpetual motion to continue, friction must be taken out of the equation.

Likewise, when we allow our lives to be swept up in thrall to the Busy Monster, we cannot help but be defeated in our pursuit of perpetual motion. We are left frustrated and resentful. After all, what are children, relationships, family, and friends if not a source of friction? What are the little mishaps that turn into treasured memories? Friction. What are the wrong turns that produce grand adventures? Friction. Put simply, when we live in perpetual motion, we leave no room for the sources of friction that have been placed in our lives to slow us down and smooth our rough edges.

This summer, I am challenging myself—and you—to fight back against the Busy Monster. Let go of the dream that you might one day become the fabled perpetual motion machine. Instead, savor food. Take time to sit down over a meal with your family or friends. Close the computer and put away your phone. Notice the food you put in your mouth. Savor faces. Even if you can give only five minutes, share a cup of morning coffee with your spouse or take a short walk with your teenage son or daughter. Give the face opposite yours your full attention for those few minutes. Savor words. Rather than rushing through a long book list, choose a line of poetry or a verse to relish all day long. Tape it to your mirror. Think about it, one word at a time. Taste every syllable. Finally, savor friction. Give yourself permission to laugh at your own mistakes. Watch your children grow and change before your eyes as they discover and smooth their own rough edges. Marvel at the beautiful humanity of the people around you.

After all, who really wants to be a perpetual motion machine? If we are honest with ourselves, I think we have to admit that the only one who stands to gain from our perpetual busyness is the one whose opinion should matter least: the Busy Monster.

Additional Resources

Classical Conversations MultiMedia. Classical Acts & Facts Science Cards. (4 sets). West End, NC: CCMM.

Ord-Hume, Arthur W. J. G. Perpetual Motion: The History of an Obsession. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1977.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Taccola_overbalanced_wheel.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Perpetuum_mobile_villard_de_honnecourt.jpg